Searching for Sarah

Sophia and Sarah Bateson’s memorial in Kells Kirkyard.

In early 2022, Grave Encounters - a volunteer research project run by the Can You Dig It community archaeology group, part of the Galloway Glens Landscape Partnership - revealed the fascinating histories behind the names on some of the gravestones in Kells kirkyard.

My own undertaking was to uncover fragments of the lives of Sarah and Sophia Bateson, who lived out their lives as servants in a family who survived bankruptcy in England to become a wealthy Galloway household.

Inscription on Sophia and Sarah’s memorial:

“Erected to the memory of Sophia BATESON a native of Yorkshire who died at Glenlochar House in this county 6th June 1869 aged 86 years, and is interred in Cross-Michael Churchyard. Also of Sarah BATESON niece of the above who died at Cairn Edward in this Parish 21st March 1895 aged 79 years. Two faithfull and beloved servants from youth till death in the family of Tottenham LEE, Esq., of Saint John's Wakefield for many years resident in this county.”

Sarah Bateson (1816?-1895) and her aunt, Sophia Bateson (1783?-1869), were born and lived their younger years in County Durham. Both joined the household of local businessman Tottenham Lee as servants (Sophia at 24 years old), and both remained in service with this family for the rest of their lives.

As with most servants of that time, little documentation of their lives survives, apart from official recordings of birth, marriage, death and wills, and the few fragments that can be gleaned or imagined from these. Sophia is the more shadowy figure; apart from the official dates and two census listings, I discovered really nothing about her or her life. With Sarah, one document unexpectedly revealed some surprises, and brought her suddenly to life for me.

Life and death with the Lee family

Born in 1794, Tottenham Lee was a lawyer, investor and businessman who came from a wealthy family. His father John Lee was a philanthropist, industrialist, lawyer and entrepreneur, and funded Britain's first public railway.

In 1841 Tottenham was living with his wife Louisa Egremont, a wealthy heiress, and six children in a fine townhouse called Newton Lodge in Wakefield, Yorkshire, along with Sophia (then 59) and Sarah (then 25), the cook, and three other servants. Following years of constant borrowing from his father-in-law, John Egremont, and then Egremont's death in 1841, Tottenham went bankrupt. Fortunately for him, Louisa had an annual income of £400 (about £55k today) and also eventually inherited a vast fortune, which, as her husband, Tottenham had free right to access, thanks to the jus mariti law (see text box below).

But by 1851, Tottenham and Louisa, plus the children, Sophia the nanny and Sarah the cook, had moved to Galloway - to Glenlee Park, a small 18th-century mansion on the banks of the Ken. The reason for the move and choosing this part of Scotland isn't known, but after Tottenham's bankruptcy shenanigans, one can imagine they perhaps wanted a fresh start away from Wakefield.

Glenlochar House

In 1861 the family, with Sarah and Sophia, is recorded as living at Overton, just north of New Galloway. Later they moved again to Glenlochar Lodge, a manor house near Crossmichael.

On 6 January 1869, Sophia died at 86 from influenza at Glenlochar, and her post-death inventory showed a total of £222 11s 6d (very approximately £30k today), most of which were her bank savings in England. Niece Sarah is named in the inventory as next of kin, and as no one is mentioned as beneficiary, it's likely that she and her brother John inherited Sophia's money.

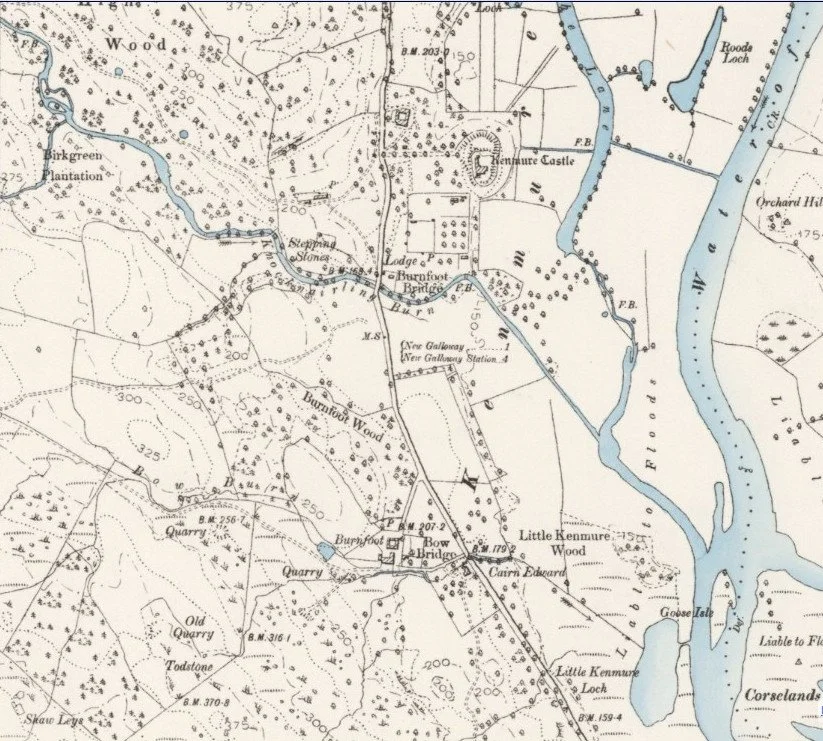

Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC-BY) licence.

In 1871 Sarah was still at Glenlochar with the family, but by 1881, whilst the Lees were listed there, Sarah isn't, and is instead recorded as living at Burnfoot Cottage. There she is "head" of the household, unmarried, and her occupation is given as "housekeeper". It's not clear if that means housekeeper in her own dwelling or still working for the Lees at Glenlochar. The Kirkcudbrightshire OS Name Books 1848-1851 list "Burnfoot: About 16 Chains S W. [South West] of Kenmure Castle A farm house &. out houses all thatched and in bad Repair. with a large farm of land attached the greatest of which is Moorland. It is the property of the heirs of the late Lord Kenmure."

This is perhaps likely to be where Sarah's cottage was. Tottenham Lee's daughter Jane Crane was by now married to John Maitland - son of the Rev James Maitland of Kells and Louisa Bellamy Gordon (niece of Adam Gordon, 8th Viscount of Kenmure), and thus the heir to Kenmure Castle and estate. In 1881 Sarah is 65 years old, so perhaps this was provided for her by the Lees and/or the Maitlands as a retirement home.

Tottenham Lee died in 1888 aged 95, outliving his wife and five of his six children (Jane Maitland lived until 1928). By 1891 Sarah Bateson is listed in the census as living again with the family - but this time with Jane, her husband and other servants at Cairn Edward, just below the Kenmure estate, and for the first time as "annuitant" (similar to pensioner). Curiously though, in her will, written in 1891, Sarah also refers to "Catherine Keir, Sick Nurse of the Royal Scottish Nursing Institute, Edinburgh, presently residing with me at Crossmichael Village". Possibly she was living in a temporary village home whilst in ill health?

On 21 March 1895, aged 79, Sarah died at Cairn Edward, of "senile decay". Present was her great-niece, nephew Thomas Greenwell's daughter, Sarah Annie Bateson (aged 24).

John Bateson, Sarah's brother

Sarah's family

Sarah's grandparents were Thomas Bateson, a wool weaver, and Sarah Huckans/Huggins. Their children were John Bateson, Sophia Bateson and Thomas Bateson, Sarah's father, who married Margaret Greenwell in Houghton-le-Spring, Co. Durham on 11 May 1812.

Thomas, an innkeeper/vintner, and Margaret lived in this mining town, and Sarah may have grown up here. Sadly, Sarah's father died in 1819, when Sarah was just three years old and her brother John six years. Her mother Margaret was a schoolmistress, who lived to 78.

Sarah's brother John Bateson became a bookbinder in Durham. He married Ann Laws in 1838, and they had 7 children (5 girls, 2 sons). Their first son, Thomas, died at just two years old. John seems to have been a prominent and well liked character.

Alice Best, wife of Thomas, Sarah's nephew

He supported several local Benefit Societies, and was "a genial and humorous companion", of "kind and unassuming disposition, being ever ready to do a generous action to any who might cross his path in the hour of need". He is described as a good singer and mimic, and "to hear and see his comicalities was a treat not to be missed".

John Bateson's son Thomas Greenwell Bateson lived in the mining village of South Hetton, working as a colliery saddler at the colliery there. He married Alice Best and they had 9 or 10 children, the largest family of his siblings. All his sisters except one married and had children.

Sarah's will: revelations and questions

Almost all the information I uncovered about Sarah and Sophia themselves was factual and impersonal. As women, and particularly as servants, virtually nothing was documented of them and their lives - articles, letters, diaries - or if these things existed, they haven't survived, as far as we know.

So I was delighted and enthralled to come across Sarah's will and testament, made on 14 March 1891, four years before she died. This not only gave me a welcome new raft of family information, but also suddenly something of her personality shone through. She briefly came alive, and I could hear her voice, and learn a little of her passions and feelings and relationships.

The first interesting thing was that Sarah left her money - a sum of £146 15s 1d (very approximately £19,729 today) - to her nephew (and executor) Thomas Greenwell and three of her five nieces, Sarah Jane, Ann and Frances. I wondered - why did she leave out her other two nieces, Margaret and Ellen? it seems rather pointed, and hinted at perhaps familial disagreements or upsets. Or was it simply that she thoughtfully perceived the four named beneficiaries as more needy of the money? Thomas, for example, had a large family to support, and Sarah Jane was working in service.

As a perhaps relevant aside, Margaret Greenwell - Sarah's mother - in her will had left £19 to her granddaughter Sarah Jane - the same niece that Sarah left money to - thus similarly singling her out from the six grandchildren. Margaret left the rest of her possessions to her two children, John and Sarah.

Jus mariti

jus mariti (latin - the right of the husband) was "the right of property originally invested in the husband on marriage in all his wife's moveables except her paraphernalia, ie clothes, jewelry and their receptacles". (Sc. 1946 A. D. Gibb Legal Terms 47).

"In the common law of Scotland there existed from medieval times until the nineteenth century a system of proprietary relations between spouses.... Marriage carried the moveable estate of the wife to the husband by an implied universal assignation known as the jus mariti ... During the marriage no steps were taken to protect the wife’s interest and the husband could deal with the “goods in communion” as if she did not exist. ... The jus mariti .... could be expressly excluded by a third party conveying or bequeathing estate to the wife. (The Effect of Marriage upon Property in Scots Law, A E Anton, 1956)

In 1881, by the Married Women's Property (Scotland) Act, the jus mariti was abolished in the case of marriages contracted after the date of the passing of the Act.

What also struck me was how Sarah firmly states: "I exclude and debar the jus mariti and all other rights of the husbands of all females taking benefit under these presents".

Although the Married Women's Property Act had abolished this law 10 years previously, it still applied to marriages that took place before the Act was passed, including those of Sarah's nieces (see text box explaining the jus mariti law).

This is such a passionate, clear statement, with strength of feeling behind it. She evidently wants to make absolutely certain that her money goes to and stays with each woman she is giving it to, and not to her husband. I wondered what was behind this - discomfort at witnessing her employer Tottenham Lee being rescued by and then living on his wife's vast inheritance, after failing spectacularly to make his own way in life and work, perhaps something more personal that she was aware of in her nieces' relationships with their husbands or maybe just that she was a woman of strong principle?

Finally, in the will Sarah states her desire "to be buried in Bamborough Churchyard and I direct my Executor to erect a tombstone over my grave at a cost of ten pounds, said stone to include the names of my Father and mother, Thomas Bateson and Margaret Bateson". I was curious to know what was behind Sarah's wish to be buried at Bamburgh, 155 miles from where she lived and died, and a good 70 miles from Durham, her home area. I'd never come across the town mentioned in all the research, so can only think that perhaps she'd visited there and formed an attachment to the area or church.

Sadly, Sarah's simple and heartfelt wishes for her burial and reunification in inscription with her parents were almost certainly never carried out. I corresponded with the minister at St Aidan's church in Bamburgh, who told me there is no record of Sarah's burial there. I felt saddened by this, and made some attempts to locate her grave; it's possible that Stone 16 at Kells Kirkyard is a memorial stone only. I tried to find other cemeteries or graveyards with a similar name, without success.

Kells Parish Kirkyard

And of course I wondered why Thomas Greenwell did not apparently carry out his aunt's last wishes. It seemed heartless and disloyal, until it occurred to me that it may have simply been that he did not know the contents of her will, and did not learn of them in time. Unless he - or an official - had read the will before or immediately upon Sarah's death, he/they could not have acted upon this particular instruction.

And it's unclear whether the Kells stone is a memorial or actual gravestone. I'm left wondering.... where does Sarah Bateson lie?

Sources: NLS, Find My Past, Family Search, Scotland's People, North East Inheritance, British Newspaper Archive, Free BMD, Ancestry UK, Sharon Course's report on the Lee family.

Sue Taylor