Farming in a Changing Landscape

The speed of land use change in Galloway is extraordinary.

In what seems like no time at all, extensive areas of traditional hill farming country have gone to commercial forestry, and given the time delay between approval and delivery of new forest projects, it’s hard to grasp the enormity of what’s coming next.

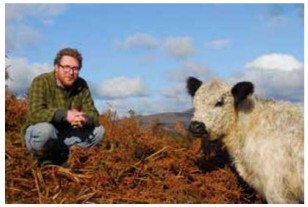

Patrick Laurie with one of his Galloways, photograph by Polly Pullar.

When I travel to other parts of the UK for work, it’s hard to convey a sense of these dramatic changes to people who have not seen it with their own eyes. In the same way, when visitors come here to see what’s happening, many are staggered by the transformation currently unfolding in the hills.

In 2010, it wasn’t unusual for hill grazing in Galloway to be bought and sold at around £850 per acre, but in recent months the same acre of land might cost seven or eight thousand pounds. Major commercial investors are battling to buy our land, and as we approach a period of uncertainty for hill farming, it’s easy to see why many farmers are taking the opportunity to sell up and get out.

The average age of a farmer in Scotland is 57, and it’s fair to say that many Galloway farmers are treating the sale of their land as an unexpectedly generous windfall in advance of their retirement. That makes sense, and it’s hard to blame people for selling now. But it also means that it’s almost impossible for younger farmers to get a foot on the ladder. Land is hard to get hold of at the best of times, but when so much of it suddenly vanishes into forestry, it’s like the future is being switched off.

In many ways I blame the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) for this mess. Several decades of supportive subsidy drove farmers to follow a single thread of income through sheep, even as those animals became less financially viable. There’s no doubt that sheep are part of the answer for hill farming systems, but it’s never sensible to place all your eggs in a single basket. Leaving the CAP, it’s no wonder that some farmers are feeling panicked – they’ve been driven into a specialised business that seems horribly uncertain, but while sheep farming as we know it today seems like an ancient practice, it’s actually quite a recent creation. Even fifty years ago, parts of most hill farms were cropped for cereals and root crops and many had pigs or cattle of some kind. The uplands used to offer a far more diverse mixture of revenue streams, but these have steadily eroded down to one.

The traditional model was more diverse, but there is an even wider range of options for modern hill farming. Hill farmers can run their sheep and cows alongside renewable energy, sustainable timber production and tourism. We’re working towards a system that will pay for hill farms to store carbon in peat, and it’s likely that future subsidies will provide proper support to protect and conserve our fantastic upland biodiversity.

We have the potential to build a really bright, diverse and exciting future for hill farming in Galloway which will dramatically boost local communities. It’s an exciting place to work, but as land continues to sell at exclusive prices to pension companies and green investors from across the world, it’s getting harder to see how we’ll ever be able to realise the true potential of our hills.

Patrick Laurie